Downloads

Download

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Review

Catalytic NOx Aftertreatment—Towards Ultra-Low NOx Mobility

Navjot Sandhu * , Xiao Yu, and Ming Zheng

Department of Mechanical, Automotive and Materials Engineering, University of Windsor, 401 Sunset Avenue, Windsor, ON N9B 3P4, Canada

* Correspondence: sandh12p@uwindsor.ca

Received: 26 January 2024

Accepted: 13 March 2024

Published: 20 March 2024

Abstract: The push for environmental protection and sustainability has led to strict emission regulations for automotive manufacturers as evident in EURO VII and EPA2027 requirements. The challenge lies in maintaining fuel efficiency and simultaneously reducing the carbon footprint while meeting future emission regulations. Nitrogen oxides represent one of the major and most regulated components of automotive emissions. The need to meet the stringent requirements regarding NOx emissions in both SI and CI engines has led to the development of a range of in-cylinder strategies and after-treatment techniques. In-cylinder NOx control strategies including charge dilution (fresh air and EGR), low-temperature combustion, and use of alternative fuels (as drop-in replacements or dual fuel operation) have proven to be highly effective in thermal NOx abatement. Aftertreatment methods are required to further reduce NOx emissions. Current catalytic aftertreatment systems for NOx mitigation in SI and CI engines include the three-way catalyst (TWC), selective catalytic reduction (SCR) and lean NOx trap (LNT). This review summarizes various approaches to NOx abatement in IC engines using aftertreatment catalysts. The mechanism, composition, operation parameters and recent advances in each after-treatment system are discussed in detail. The challenges to the current after-treatment scenario, such as cold start light off, catalyst poisoning and the limits of current aftertreatment solutions in relevance to the EURO VII and 2026 EPA requirements are highlighted. Lastly, recommendations are made for future aftertreatment systems to achieve ultra-low NOx emissions.

Keywords:

three-way catalyst SCR NO<sub>x</sub> aftertreatment ultra-low NO<sub>x</sub> lean NO<sub>x</sub> trap1. Introduction

The modern automotive industry is characterized by a diverse range of propulsion systems and energy sources including internal combustion (IC) engines using a wide variety of hydrocarbon (HC) based fuels, hydrogen fuel cells and battery-motor systems. Driven by the increasing focus on efficiency and environmental sustainability, electric vehicles and hydrogen fuel cells have garnered significant attention as greener alternatives. However, owing to the high energy density and portability of HC fuels, internal combustion engines and gas turbines, continue to be indispensable elements of the transportation and energy sectors [1,2]. This reliance on the combustion of HC fuels highlights the significance of reducing tailpipe emissions and enhancing fuel efficiency for energy and environmental sustainability. The emission from combustion-based powertrains primarily includes solid particles (10–100 nm in diameter) and gaseous pollutants, such as oxides of nitrogen (NOx), unburnt/partially-burnt hydrocarbons, CO, oxides of fuel-borne sulphur (SOx), CO2 and water vapor. Governments worldwide have recognized the need to curtail the environmental impact of the emissions from transportation sector, leading to the imposition of increasingly stringent emission and fuel economy standards.

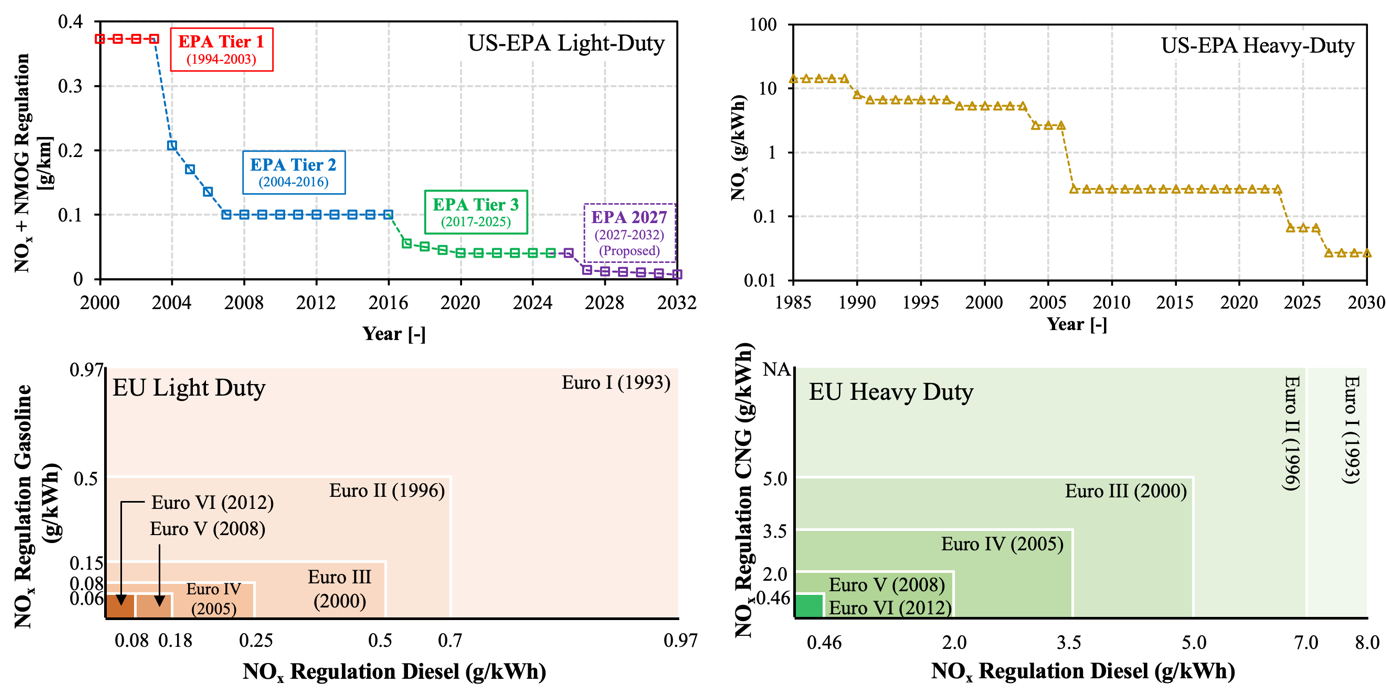

Initially, when the emission regulations were implemented between 1988 and 2006, the US-EPA and European Commission primarily focused on the NOx reduction [3-7]. However, starting from 2007, PM emission regulations became stringent for heavy-duty vehicles and were later introduced for light-duty vehicles as well, requiring vehicle manufacturers to use diesel particulate filters (DPF) and subsequently, gasoline particulate filters (GPF) to meet the emission regulations. The European and US NOx emission regulations for light-duty and heavy-duty vehicles have been summarized in Figure 1 [4-9]. In US, Tier 1 standards were published in 1991 for light-duty vehicles and were phased in from 1994 to 1997. These standards capped the NOx + NMOG emissions at ~0.37 g/km [5]. Tier 2 standards were adopted in 1999 with a phase-in implementation schedule from 2004 to 2007. These standards mandated a cap of ~0.1 g/km on NOx emissions, a ~70% reduction compared to the Tier 1 standards [6]. Subsequently, Tier 3 standards further lowered the NOx limits by another 60% to 0.04 g/km [7]. Overall, these regulations represent a 95% reduction in NOx emissions for light-duty vehicles in the last 3 decades. Concurrently, The European regulatory bodies have also introduced progressively stricter regulations limiting NOx emissions from Light duty gasoline and diesel vehicles at 0.06 g/km (Euro VI regulations) [10], a reduction of 94% since 1989. In addition to NOx regulations, the sulphur levels in gasoline were required to be reduced to 30 ppm in 2006, which were later tightened to 10 ppm at the beginning of 2017 [11].

Figure 1. US and EU NOx regulations.

For heavy-duty vehicles, the NOx emission regulations were introduced in 1985 and 1993 by the US-EPA and the European Commission, respectively. In Europe, the initial regulations were introduced for diesel engines but were later extended for compressed natural gas (CNG) engines as well. In US, the NOx standards have been capped at 0.27 g/kWh following five mandated reductions since 1985 [12]. Similarly, the European counterparts have limited the heavy-duty NOx emissions to 0.46 g/kWh for both diesel and CNG vehicles [13]. These represent a combined 98% and 95% NOx reduction since the introduction of emission regulations in the US and EU, respectively. Additionally, diesel fuel with a maximum sulphur level of 15 ppm was made available for highway use in 2006. Sulphur was recommended to be reduced to 15 ppm (ultralow sulphur diesel) as of June 2010 for on-road fuel and in June 2012 for locomotive and marine fuels [14].

The proposed EURO VII and EPA2027 and beyond emission regulations present a further 40-70% reduction in NOx emissions and ~50% reduction in CO emissions for the light and medium-duty sectors [8]. Additionally, the proposed EPA 2027-2032 emission regulation roadmap also includes up to 56% GHG reduction for Light duty and 44% GHG reduction for medium duty sector by 2032 [9]. Moreover, the new proposed emission standards include formaldehyde and ammonia as regulated components of the engine exhaust.

In addition to the on-road vehicles, locomotive and marine sectors account for a significant portion of the global transportation NOx emissions. In 2018, ~25% of the total NOx emission in EU were accounted for by the marine transportation sector [15]. Even though the marine vessels and locomotives are far fewer in number as compared to the automotive vehicles, large size and long operating duration, combined with relatively poor quality of the marine fuel contributes to the escalated emissions [16]. To address this issue, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and various governments have implemented the Regulations for the Prevention of Air Pollution from ships and locomotive engines. Present regulations mandate a 5.4–11 g/kWh NOx emissions cap from the MY2016 onwards ships depending on the engine displacement and power [17]. Locomotive engines experience similar emission standards with 1.8–15.8 g/kWh mandated NOx emission cap via Tier 4 EPA regulations depending on the engine model year [18]. However, because of the long service life of marine and locomotive engines and the relatively lenient regulations as compared to on-road automotive vehicles, NOx control in marine engines has largely been relegated to a simple yet effective lean exhaust aftertreatment system consisting of a particulate filter (DPF) and a urea based selective catalytic reduction (SCR) system [17,19]. Locomotive engines on the other hand, mostly operate without a dedicated aftertreatment system for NOx reduction. Nevertheless, the introduction of EPA Tier 4 regulations in 2015 were intended at the introduction of the exhaust aftertreatment for locomotives to curb the emissions [18].

Compliance with the much stricter on-road vehicle emission standards has prompted extensive research into a range of strategies, including ignition, injection and combustion control, innovations in exhaust aftertreatment technologies, and exploration of alternative renewable fuels. The NOx mitigation strategies in IC engines can be largely divided into two categories: prevention of NOx formation and reduction of NOx emissions. NOx formation in IC engines follows thermal and chemical NOx pathways. Thermal NOx, formed because of the high combustion temperature (>1700 K), accounts for the major portion of engine-out NOx emissions. Most in-cylinder strategies including exhaust gas recirculation (EGR), combustion control and use of alternative fuels reduces the NOx formation by lowering the combustion temperature, thereby disrupting the thermal NOx formation pathway [20-22]. The exhaust aftertreatment system is responsible for the catalytic reduction of the NOx formed during the combustion process. Different catalytic approaches to NOx mitigation employ a same principle of NOx reduction: using reducing species, either already present in the engine exhaust (HCs and CO) or independently injected into the exhaust stream upstream of the catalyst section (Urea/NH3 or HCs), to convert NOx into benign nitrogen gas. The platinum group metals (PGMs) and auxiliary compounds (Ceria, barium oxides, zeolites, etc.) aid in selectively promoting and catalysing the reduction reactions. Exhaust aftertreatment, combined with charge dilution via EGR has been the primary NOx control methodology in IC engines for past decades.

The implementation of three-way catalyst (TWC) provided a simple, robust, and relatively economical solution for exhaust emission control in near stoichiometric operation engines (spark ignition engines). With a single catalyst controlling oxidation and reduction of emission species at a high conversion efficiency and without the requirement of additional reagents, TWC presents a simple, yet effective aftertreatment system design. Currently, TWC is the most prevalent aftertreatment solution for light and medium-duty SI engines. The “simultaneous” reductive and oxidative nature of the reactions on the TWC necessitates a pulsed lean-rich operation of the engine, confining the catalyst operation to near stoichiometric applications. For lean-burn applications, the presence of excess oxygen in the exhaust limits the NOx reduction efficiency of TWC, necessitating additional strategies for NOx mitigation. The development of a cost-effective catalytic converter system for lean-burn SI engines remains a significant challenge.

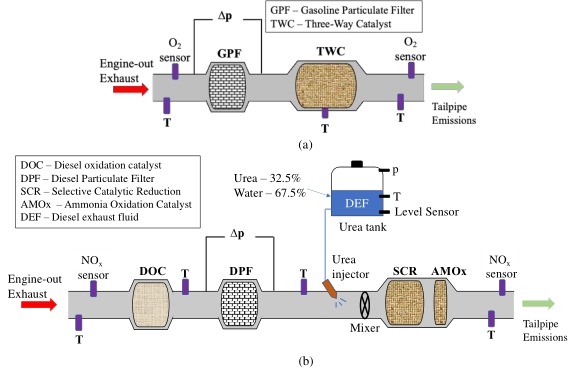

For lean burn engines, the aftertreatment system is relatively complicated, consisting of multiple catalysts controlling the oxidation and reduction of the exhaust species. A lean burn aftertreatment system consists of three major components in addition to auxiliary systems: a particulate filter (DPF), an oxidation catalyst (typically, diesel oxidation catalyst) and a NOx reduction catalyst (lean NOx trap or selective catalytic reduction catalyst). Schematics of typical TWC-based stoichiometric and SCR-based lean burn aftertreatment systems are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Typical (a) TWC-based stoichiometric and (b) SCR-based lean burn aftertreatment systems.

Selective catalytic reduction (SCR) and lean-NOx trap (LNT) catalysts are the two major lean-burn NOx abatement aftertreatment technologies that have been widely adopted for vehicular and stationary applications. Both strategies use additional reducing agents injected into the tailpipe to convert NOx and exhibit an overall high NOx reduction efficiency (>90%). Direct NOx breakdown and conversion using PGMs, metal oxides, zeolites and perovskites have also been investigated [23,24]. However, owing to challenges including low conversion efficiency at engine-relevant temperatures (<1000 K), low durability, and minimal resistance to catalytic poisoning, direct NO catalysts have not seen much development for vehicular or stationary engine applications [23]. While TWC and lean burn catalysts have proven to be effective in meeting the present emission standards, these standalone, single-stage catalysts may not be adequate to fulfill the forthcoming EU and U.S. regulations in 2027. The lean-burn engine appears to be an attractive solution combining low fuel consumption and low CO2 emissions. Although the lean burn engine adds significant complexity to the aftertreatment system, the additional efficiency and emission advantages from the lean burn [25,26], combined with the stricter emission mandates may lead to the shift towards a dedicated system for catalytic NOx mitigation.

Different methods of catalytic NOx abatement have been researched extensively over the past few decades, dealing with various aspects including novel catalytic formulations, reaction mechanisms, different reducing agents, operating conditions of the catalyst and combination of in-cylinder emission control with the aftertreatment strategies. Overall, no major breakthrough has been put forward regarding the catalyst design for gasoline and diesel-powered vehicles since the emergence of three-way catalysts [14]. However, the efficiency of the existing catalysts has improved significantly following the continuous research and development efforts into the exhaust aftertreatment. In addition to the established de-NOx techonologies including SCR, LNT and TWC catalysts, novel and experimental technologies like plasma assisted low temperature NOx reduction [27,28] and electrochemical NOx reduction [29,30] are also an area of extensive research.

The present review aims to summarize the technological aspects of the various approaches to catalytic NOx mitigation in IC engines that could aid in improving the performances of the existing technologies or the development of alternative systems running under lean-burn conditions. The mechanism, composition, operation parameters and recent advances in each aftertreatment system are discussed in detail. The challenges to the current aftertreatment scenario, including cold start light off, catalyst poisoning and the limits of the current aftertreatment solutions in relevance to the EURO VII and EPA2027 requirements are highlighted and recommendations are made for future aftertreatment systems to achieve ultra-low NOx emissions.

2. Aftertreatment Methods

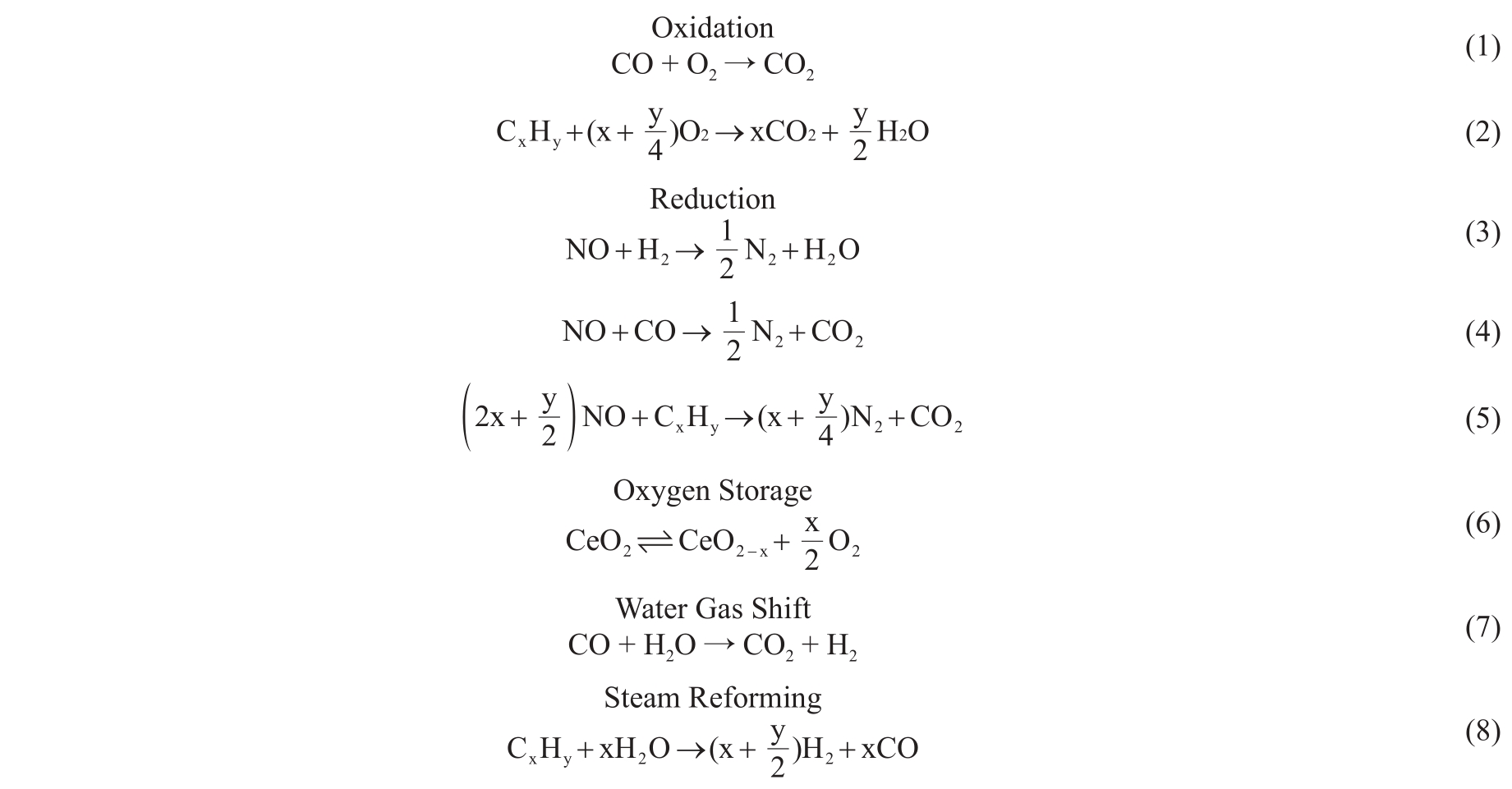

2.1. Three-Way Catalyst

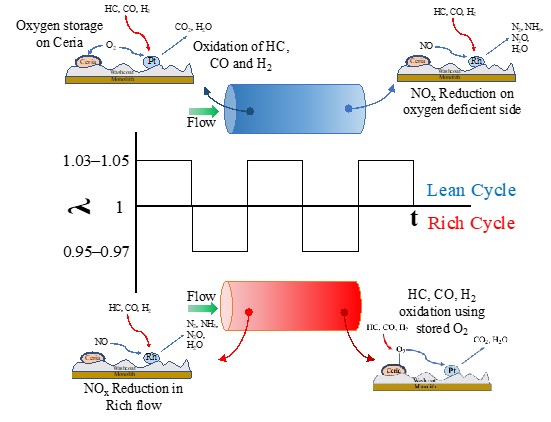

The adoption of TWC converters corresponded to a first major breakthrough in conventional aftertreatment solutions [14] and has provided remarkable results in the past three decades in terms of atmospheric pollutant abatement under complex running conditions. The operating principle of a TWC converter is illustrated in Figure 3. A TWC works under transient lean-rich oscillating (~±3–5% in the vicinity of λ = 1) conditions controlled by the engine with the feedback from the exhaust lambda sensor and can maintain extremely high conversion efficiencies of greater than 95% for CO, HC and NOx emissions simultaneously [31]. The oxygen storage capability (OSC) of ceria-containing catalysts facilitates oxygen storage during lean operating conditions, thereby promoting NOx conversion. Subsequently, it releases stored oxygen under rich conditions through reactions with carbon monoxide, hydrogen, or hydrocarbons. During the lean period, at the reaction front on the catalyst, the excess oxygen from the exhaust gas oxidizes the CO and HC species and simultaneously gets stored on the ceria. The rich gas mixture downstream of the reaction front (because of the oxygen storage preceding the reaction front), helps in NOx reduction. The stored O2 on the catalyst is utilized during the rich period on the latter part of the catalyst to oxidize CO and HC species. Major reactions on a TWC converter can be summarized as follows [32]:

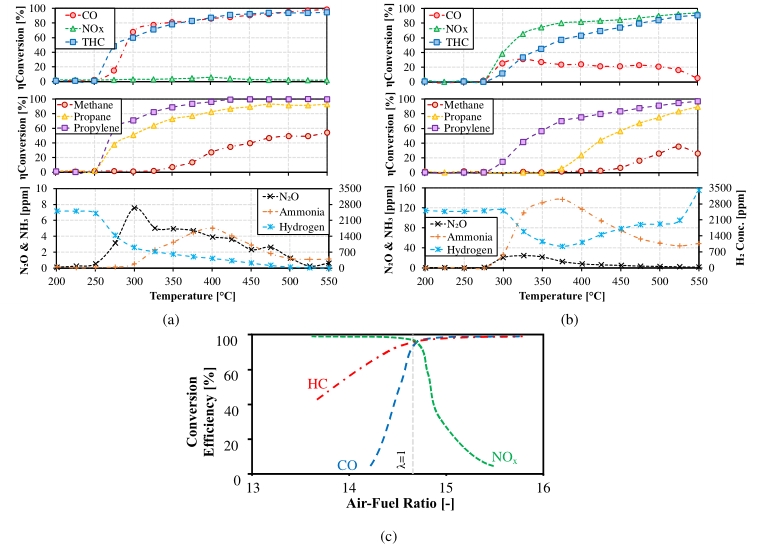

The conversion performance of TWC is affected by several factors including the monolith and washcoat composition, PGM and ceria loading, catalyst and flow temperature, exhaust gas composition, space velocity, catalyst aging and potential fouling [33]. Typical light-off performance and the influence of air-fuel ratio (exhaust gas composition) on the TWC are presented in Figure 4 [31,34]. Typical automotive TWCs achieve light-off between 200 °C and 300 °C catalyst temperature [35,36]. PGM and ceria loading, and catalyst aging have been found to have a significant effect on the TWC light-off performance [37]. The catalyst favours oxidation reactions under lean conditions, with minimal NOx reduction, and reductive reactions under rich conditions because of the ready availability of reducing agents in the form of unburnt HCs, CO and H2. In addition to the characteristic oxidation and reduction reactions, water gas shift and steam reforming reactions have a significant influence over the conversion performance and product selectivity, especially under rich conditions [32]. CO and H2 generated as the result of these reactions promote NOx reduction and NH3 formation on the catalyst under rich conditions. N2O formation is limited to incomplete NOx conversion at relatively low catalyst temperatures.

The combination of PGM doped on the catalyst (mainly Pt, Pd and Rh) ensures a quasi-complete conversion of the emission components. Platinum (Pt) and Palladium (Pd) play crucial roles in the oxidative component of three-way catalysis, whereas Rhodium (Rh) is essential for controlling NOx emissions [38,39]. The decision to use Pt or Pd is primarily driven by economic factors. In the 1990s, Pd was more prevalent due to its lower cost [40]. However, escalating demand for Pd led to a significant price increase, prompting the development of Pt-based formulations as an alternative [41]. It is important to emphasize that Pt and Pd are not interchangeable without considering other design factors. Pd is typically less stable than Pt, requiring careful consideration in the formulation process [42]. Among the three metals, Rh is the most expensive, with approximately 80% of global Rh demand attributed to TWC applications [43]. This high cost has spurred the development of low-Rh formulations. Although rhodium-free Pd-only TWCs have been created, they often exhibit limited NOx removal capabilities [41,44]. The economic considerations and performance characteristics of each metal influence the selection and formulation of catalysts for optimal three-way catalysis. More novel catalyst designs such as the use of bimetallic alloys show potential in reducing Rh loading without sacrificing performance [45].

Figure 3. Operating principle of TWC converter under alternative lean-rich oscillations.

Ceria has traditionally been utilized as an additive in TWC converters due to its capacity to store oxygen, enhance the dispersion of PGMs on the catalytic washcoat, and stabilize their distribution [46,47]. Ceria also serves as a promoter for various catalytic reactions on PGM particles, including the water gas shift and steam reforming reactions [47]. Recent advancements involving the addition of ceria-zirconia mixed oxides to the washcoat have resulted in notable improvements in the oxygen storage capacity of the TWC catalysts [48,49]. Moreover, these mixed oxides enhance the low-temperature conversion efficiency of PGMs, particularly during cold-start engine conditions. Studies have shown that the Ce-Zr catalyst exhibits improved light-off performance for CO and HC oxidation. Typically, ceria-zirconia materials with approximately 40–60% ceria content have proven to exhibit the highest oxygen storage capacity (OSC) [50,51]. However, the reduction reactions involving Rh face challenges in terms of NOx conversion at low light-off temperatures resulting from Ce-Zr doping in the washcoat. The low conversion levels on unpromoted Rh-based catalysts at low temperatures are typically accompanied by a significant production of nitrous oxide (N2O) due to incomplete reduction of NOx on the catalyst [52].

The dispersal and spatial alignment of PGM on the catalyst are important for the efficient functioning of the TWC. A well-dispersed PGM configuration in the vicinity of Ceria allows for an effective utilization of stored oxygen and aids in avoiding the alloying of different PGMs at higher temperatures resulting in the diminished activity of PGMs [53]. The PGM distribution has vastly improved in the past decade with the development of advanced impregnation techniques to avoid alloying effect during three-way operating conditions. Typically, noble metals are well-dispersed after impregnation of highly porous alumina wash-coat on ceramic honeycomb structures or monoliths. The wash-coat is essentially composed of alumina (approx. 5–15 wt% of the monolith), with specific surface areas ranging between 100 to 200 m2g-1 [54]. Due to exposure to high temperatures up to ~1000 °C in full engine load conditions, lanthanum and barium additives were subsequently added as stabilizers [54].

Figure 4. Typical light-off performance under (a) lean conditions (λ = 1.1), (b) rich conditions (λ = 0.96) and (c) the influence of air-fuel ratio on the TWC [31,34].

Deactivation of TWC over a period of operation can result from multiple thermal and chemical processes. Thermal processes include PGM sintering or alloying at high temperatures, changes to the supporting substrate, interactions between PGM and base metals, oxidation, and migration or change in orientations of PGMs. Chemical deactivation is a result of non-reversible contaminant accumulation (through chemical interaction or physical deposition) on active sites inhibiting or competing with the catalytic reactions. Lubricating additives to the engine oil are the main source of phosphorus, zinc and partially sulphur contaminants [55]. Although the presence of sulphur in automotive fuels has been minimized in the last decades due to environmental restrictions, the presence of small quantities is unavoidable. Hence, the sulphur poisoning in TWC can be largely attributed to the sulphur content from the fuel. The main compounds formed by the contaminants at the TWC operational conditions are phosphates (AlPO4, Zn2P2O7) [56], sulphates (Ce2(SO4)3, CeOSO4) [57,58] and oxides, with the sulphates being the primary contributing factors for the loss of catalyst activity [59]. Studies have shown that sulphur poisoning in TWC affects the ceria-related functions of the catalyst, namely the oxygen storage capacity and hydrogen formation from water gas shift and steam reforming pathways [60]. Under rich conditions, there are indications that H2S can poison the PGMs by the formation of sulphides [59].

2.2. Lean NOx Trap

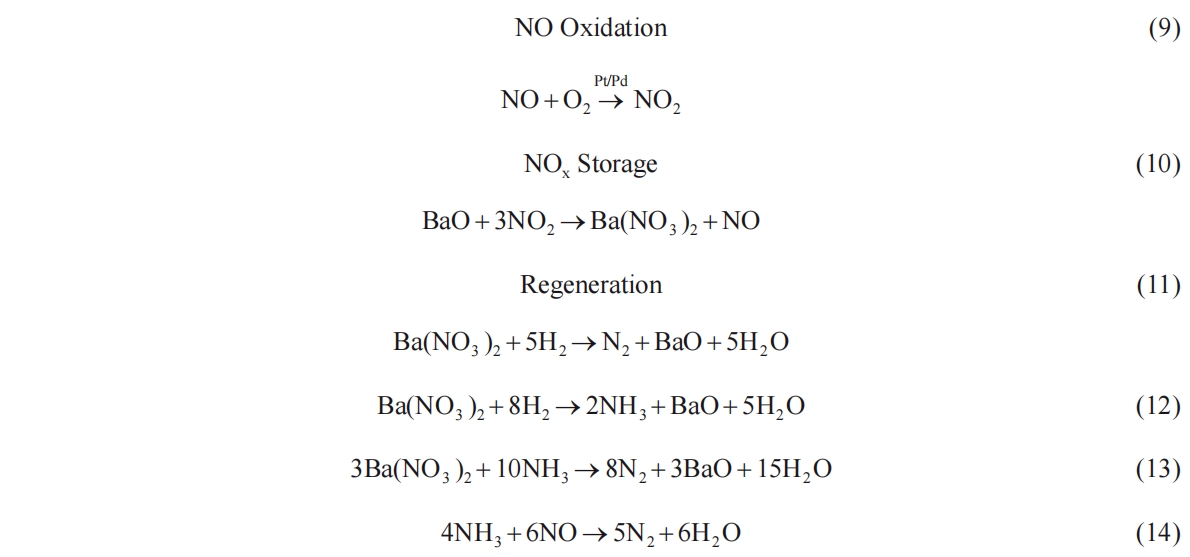

Fundamentally, Lean NOx trap (LNT) or NOx storage & reduction (NSR) catalysts consist of three-way catalysts modified by barium addition for NOx storage. The NOx storage on barium (Ba) compounds decouples the NOx reduction from the oxygen storage on ceria and significantly prolongs the lean period (up to several minutes), which is suitable for NOx reduction for lean burn combustion strategies. A much shorter (a few seconds) fuel-rich period is necessary to regenerate the LNT catalyst and convert the stored NOx mainly into N2. During the lean period, engine-out NOx is adsorbed on the alkaline metal storage sites (typically Ba2+, as BaO or BaCO3) as nitrites and nitrates. As the NOx storage sites get progressively occupied, NOx slip downstream of LNT is observed. When the storage capacity of the catalyst is saturated or a predetermined amount of NOx slip is observed downstream of LNT, the rich period is initiated by supplemental fuel injection upstream of the LNT, converting the stored NOx into N2, with trace amounts of N2O and NH3 [61]. The regeneration of the catalyst frees the storage sites for NOx adsorption in subsequent lean periods. The operating principle of the LNT catalyst is illustrated in Figure 5. Typically, the LNT catalyst contains storage materials (e.g., BaO/BaCO3, CeO2), support materials (e.g., Al2O3 and CeZrOx), and PGMs (e.g., Pt, Pd, and Rh) [62]. Pt and Pd mainly oxidize NO to NO2 for storage, whereas Rh aids in NOx reduction and combined with Ceria, promotes water gas shift reactions and steam reforming reactions for H2 formation [47,63]. The NOx storage and oxidation sites are usually situated in close proximity. Major reactions on LNT can be summarized as follows [64]:

Figure 5. Operating Principle of LNT Catalyst.

The use of onboard fuel for LNT regeneration as reductant induces a fuel penalty because of periodic fuel injection events in the aftertreatment system. This fuel penalty (additional fuel energy required for LNT regeneration) can be as high as 2.5% for conventional LNT operation [65]. The conventional high-temperature combustion in IC engines results in significant NOx generation that can quickly saturate the LNT catalyst, requiring frequent regeneration events that increase the fuel penalty. Lowering the combustion temperature by using a moderate level of EGR can significantly curtail the engine-out NOx emissions without a considerable impact on the engine performance, thus prolonging the lean NOx storage period and reducing the frequency of required regeneration cycles. This combination of in-cylinder and tailpipe NOx mitigation, termed as “long breathing” LNT strategy, has achieved low tailpipe NOx emissions with diminished fuel penalty as low as 0.3% [65-67].

The dispersion and spatial distribution of alkaline metal compounds and PGMs have a significant effect on the storage and reduction reactions on LNT [62]. NO2 has a higher affinity for adsorption on LNT as compared to NO. Consequently, NO oxidation over the Pt/Pd sites is a key step in NOx adsorption [68]. The availability of alkaline metal storage sites in the vicinity of Pt/Pd promotes the storage process in the lean period. Similarly, accessibility to Rh near storage sites aids in NOx reduction in the rich period. Ceria-doped on the catalyst washcoat, stores oxygen during the lean period and aids in the conversion of excess HC, CO and H2 from the reductant injection in the rich period. The exothermic oxidation reaction further increases the catalyst temperature during the regeneration period, thereby improving the NOx conversion efficiency. Additionally, Ceria promotes H2 formation under rich conditions via the water-gas shift reaction, which can be used for LNT catalyst regeneration and desulfation [69]. However, the presence of ceria on the catalyst increases the N2O (a potent greenhouse gas) selectivity during NOx conversion and reduces the NH3 formation [70]. Generally, the reduction in NH3 formation is beneficial. It eliminates the need for a cleanup catalyst, but the low NH3 yield can prove detrimental to the aftertreatment system configurations that combine LNT with passive SCR catalysts.

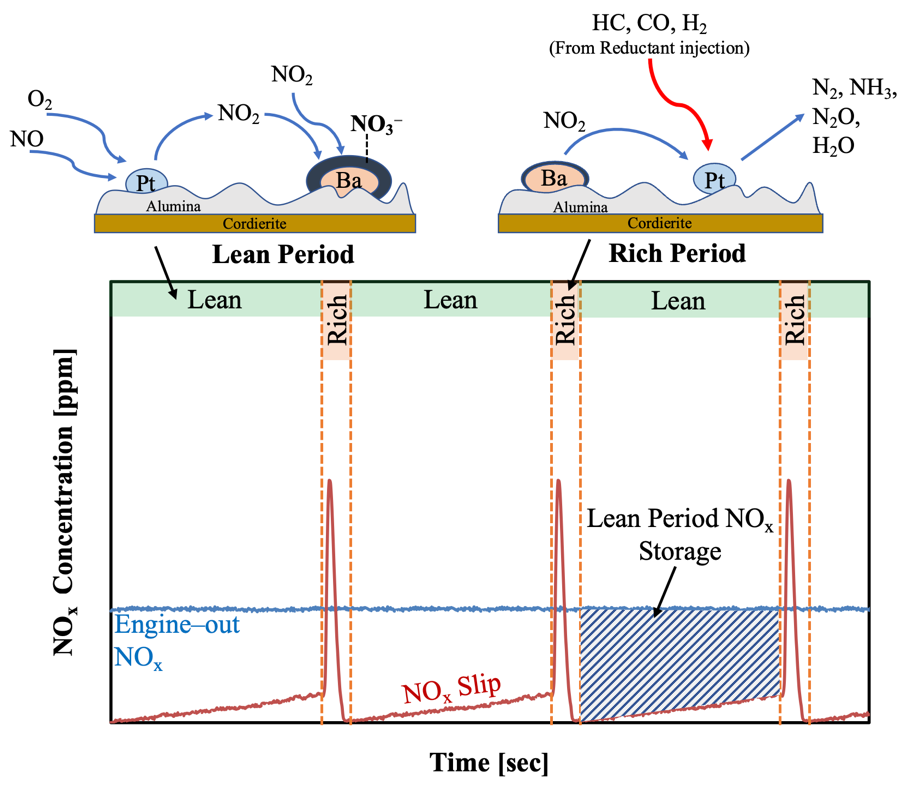

NOx storage and conversion efficiencies of LNT catalysts have a major dependence on the catalyst temperature and activity of the reductant. NOx storage and conversion efficiencies of a BaCO3/CeO2-based LNT while using 1.8g gasoline, ethanol and DME as reductants are illustrated in Figure 6. The variation of NOx storage efficiency largely follows the activity and stability of BaCO3 and Ba(NO3)2 with temperature. NOx storage initially increases as the conversion of barium carbonate to barium nitrate increases with temperature, reaching a maximum around 350 °C. At and beyond 400 °C, barium nitrate becomes unstable, resulting in the thermal release of NOx, thereby progressively deteriorating the NOx storage efficiency. NOx conversion efficiency increases unidirectionally with the increase in temperature [71,72].

Figure 6. Variation of NOx storage and conversion efficiencies of a BaCO3/CeO2-based LNT with temperature using 1.8 g gasoline, ethanol and DME as reductants.

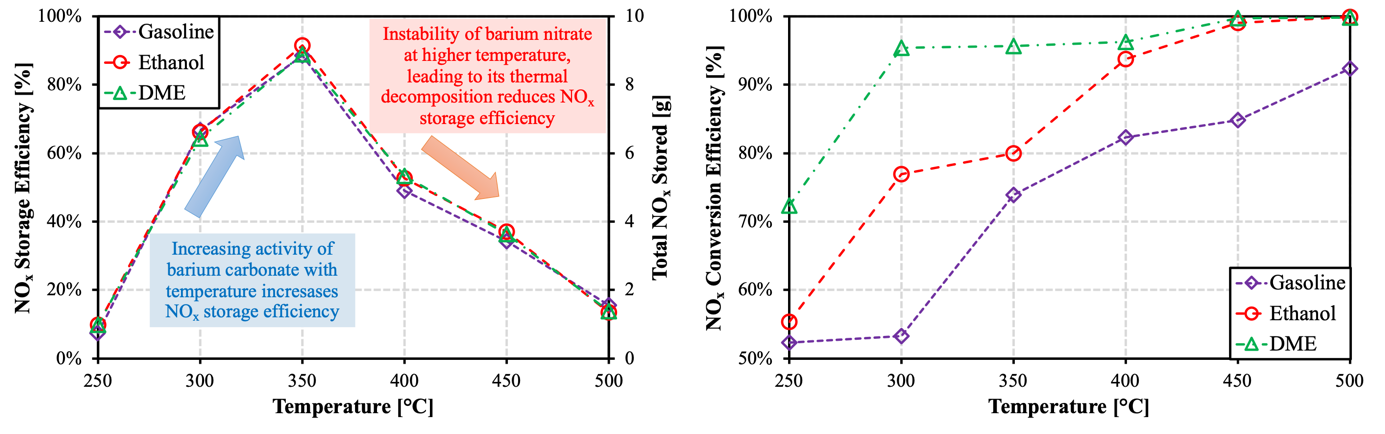

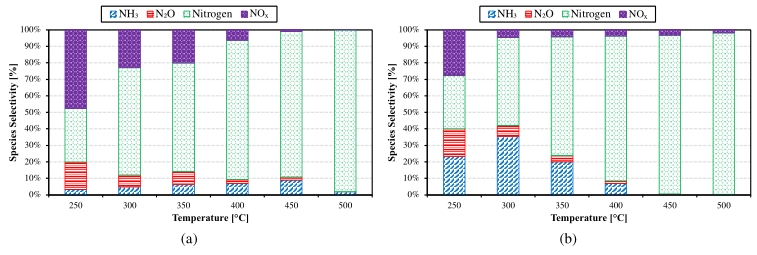

Studies have shown that at lower temperatures (<300 °C), the NOx regeneration and conversion processes are slow and kinetically limiting, favouring a longer rich regeneration period irrespective of reductant quantity. As the temperature increases, the NOx conversion rate and efficiency increase and the NOx storage becomes the limiting factor for LNT operation at and beyond 400 °C [73]. Product selectivity of the LNT towards N2O and NH3 is primarily a function of temperature. Selectivity to NH3 and N2O decreases with increasing temperature irrespective of the reductant used [73]. While the reductants have been shown to have a minor impact on the product selectivities, the differences observed are largely because of variations in the chemical reactivities of the reductants with temperature (Figure 7). N2O is typically formed during low-temperature reduction of NOx by either HC, H2, CO or NH3 [52]. As the reaction temperature increases, the product selectivity shifts towards N2 from N2O. Ammonia, on the other hand, is primarily formed as a result of the reduction of slow-releasing NOx from barium nitrate with hydrogen on the precious metal sites [74]. As the temperature increases, the availability of hydrogen increases because of the steam reforming and water gas shift reactions. The hydrogen released further promotes the formation of ammonia on the precious metal sites. However, some of the ammonia formed by the delayed NOx release in the front part of the catalyst reacts with the NOx released on the latter half of the catalyst to be oxidized into N2 and H2O according to the reaction (12) [75]. At low temperatures, the reaction forms a mixture of N2O and N2, further resulting in a relatively high N2O selectivity. As the temperature increases, ammonia generation decreases because the thermal decomposition of ammonia leads to a reduction in stable ammonia generation on the catalyst [76]. The rate of consumption of NH3 for NOx reduction competes with other reducing species. The higher the H2 formation from HC and CO (from steam reforming and water gas shift reactions), the higher the tendency of ammonia formation. Simultaneously, higher reactivity and H2 formation of HC species leads to a faster reaction front, that leaves less NOx for reaction with latter formed NH3. This can lead to less consumption of the formed NH3 and higher ammonia slip. While in most cases, the ammonia slip past LNT is another unwanted byproduct requiring a cleanup catalyst, coupling the high NH3 yield LNT with a passive SCR catalyst has shown promising avenues for further NOx reduction.

Figure 7. Product selectivity on a BaCO3/CeO2 LNT using 1.8 g (a) ethanol and (b) DME as reductants.

The primary constraints associated with NOx-trap technology pertain to the catalyst’s tolerance to sulphur and its thermal stability. The catalyst’s storage capacity is diminished by the formation of sulphates on its surface. Although this poisoning effect is reversible, the required desulfation conditions are relatively severe, involving temperatures around 600–700 °C under partially rich conditions, leading to thermal aging of the catalyst [77]. It is widely acknowledged that exposure to SO2, the predominant sulphur species in lean conditions, primarily results in the formation of barium sulphate (BaSO4), which diminishes the NOx storage capacity [78,79]. The formation of crystallized barium sulphates, presents a greater challenge, as they are more resistant to removal compared to surface sulphates with weaker binding [77].

Owing to the high conversion efficiency of the urea-SCR technology, lack of stringent ammonia regulations, the high manufacturing cost of LNT (because of Pt doping) and the fuel penalty associated with the LNT, the latter has been largely phased out from the lean burn aftertreatment scenario in favour of urea-SCR aftertreatment. Currently, urea-SCR is the most prevalent NOx mitigation catalyst used for lean burn engines.

2.3. Selective Catalytic Reduction

Selective catalytic reduction of NOx using NH3 as reducing agent was originally developed for stationary applications (e.g., power generation plants). It was first introduced in automotive vehicles in the late 1970s in Japan. Following the early adoption for vehicular applications in 1985 in Germany, Urea-based SCR systems have emerged as the primary NOx aftertreatment catalyst for compression ignition engines in response to the enforcement of progressively more stringent regulations on NOx emissions [80,81]. The urea-SCR system uses NH3 as the primary reductant, which is derived from an aqueous solution of urea. Urea solution is used to mitigate challenges associated with the storage, toxicity, and safety of gaseous NH3 [82,83]. The typical configuration of the urea-SCR system installed in diesel vehicles has been demonstrated in Figure 2b. Urea-SCR uses an aqueous solution of 32.5% of high-purity urea (by weight) in deionized water. The urea solution is injected and atomized in the exhaust stream. Ammonia is extracted from the urea solution via the following processes [84]:

While the aqueous solution of urea has proven effective in ammonia generation for SCR catalysts, some challenges remain unsolved. Decomposition of urea requires 170 °C–180 °C temperatures, limiting the availability of NH3 during engine cold start [13]. Insufficient mixing during urea injection and evaporation results in the deposition of solid urea crystals along the exhaust pipe and the catalyst surface, which may lead to pore blockage and catalyst deactivation [85]. Additionally, the deposited urea crystals can decompose at higher temperatures leading to excessive uncontrolled NH3 generation resulting in significant NH3 slip in the tailpipe exhaust gas. Strategies to overcome these shortcomings have been a major focus of recent studies [86]. Catalytic hydrolysis of urea, using a hydrolysis catalyst before SCR, for ammonia extraction has been investigated for effective ammonia generation pre-SCR [87]. Additionally, the replacement of aqueous urea with different dosing media such as solid urea, ammonium formate, ammonium carbamate, guanidinium salts, and metal-amine chlorides are being explored [13].

The reduction of NOx by the urea-SCR process occurs in three steps, including relatively fast and slow reactions. The molar ratios of NO, NO2 and NH3 determine the dominant reaction routes. These reactions are summarized as follows [81]:

The major constituents of engine-out NOx are NO and NO2 in approximately 90% to 10 % ratio, resulting in the standard SCR reaction (16) being the dominating pathway for SCR operation [88]. However, the relatively slower reaction rate of the standard SCR reaction significantly decreases the SCR efficacy. The faster reaction pathway (17) requires the NOx composition to be in an equimolar NO/NO2 ratio [89-91]. Low-temperature combustion strategies in lean burn engines promote in-cylinder NO to NO2 conversion resulting in a significantly higher NO2 concentration of up to 40% of total NOx emission [92]. For conventional high-temperature combustion in engines, the presence of an oxidation catalyst, DOC, upstream of the SCR accelerates the NO to NO2 conversion in the lean exhaust, thereby promoting the SCR operation primarily through the faster route. In addition to the aforementioned reactions, a different set of unwanted reaction pathways can lead to ammonia oxidation and decomposition at high temperatures (>450 °C) and the formation of ammonium nitrate at low temperatures (<180 °C) [81]. These reactions constrain the operation of urea-SCR within a temperature range of 200 °C–500 °C. At the lower end of the temperature range (~200 °C), the NO can react with the ammonium nitrate to form NO2, stimulating the fast reaction pathway [93]. Additionally, at high NO/NH3 ratios, potentially resulting from poor mixing or sub-optimal performance of the urea dosing system, the standard SCR reaction (16) may proceed through a different pathway resulting in N2O formation instead of N2 [93].

Over the last few decades, copper (Cu) and iron (Fe) ion-exchanged ZSM-5 zeolites have emerged as popular catalytic active phases for SCR owing to their excellent NOx reduction performance, thermal stability, resistance to sulphur poisoning and relatively lower costs [94]. The main difference between the two zeolites is the active operating temperature range for NOx reduction. Cu/ZSM-5 is active at relatively lower temperatures of ~350 °C, whereas Fe/ZSM-5 prefers a much higher temperature of ~500 °C. To widen the effective temperature range, a combination of Fe and Cu active phases is used. Studies have reported an improvement in NH3 activity, N2 selectivity, and hydrothermal stability from the combination [95,96].

Hydrothermal aging and HC poisoning are two primary factors leading to the loss of catalytic activity. Hydrothermal aging causes the dealumination of zeolites and agglomeration of active metal sites (Cu or Fe) [97]. Alkaline earth metal additives including Na, K, Ca and Zn have been shown to increase the thermal stability and resistance to hydrothermal aging in SCR catalysts [98,99]. Unburnt HC species (ranging from light to heavy HCs) inhibit the catalytic activity of SCR through different pathways including direct absorption and coke deposition on active sites, competition with NH3 for active sites, and formation of unwanted reaction intermediates [96,100,101]. Ethane (C2H4), propane (C3H8) and propene (C3H6) are known to have a poisoning effect on Cu-SCRs whereas Fe-SCRs are poisoned by propene (C3H6) [62].

A major drawback of the urea-SCR system is the requirement of additional space and complexity arising from urea storage and injection equipment. Therefore, the use of HC, CO and H2 have been investigated as reductants for NOx. Key limitations of these systems arise from the poor affinity of the reducing material toward reaction with NOx in the presence of O2, owing to the competition from the oxidizing reactions [102]. Different zeolites and PGMs have been tested for their effectiveness in improving the reaction selectivity and catalyzing NOx reduction. HC-SCR with 2Cu/ZSM-5 has been shown to exhibit a NOx conversion efficiency as high as 70% at 450 °C using butane (C4H10) but is prone to hydrothermal aging [102]. Additionally, the catalytic activity of HC-SCR is acutely affected by the chemical properties of the HC species [103]. PGMs including Pd, Pt and Rh show poor catalytic activity towards NOx reduction in the presence of O2 for both HC and CO-SCR applications [104]. However, Ag and Ba-Ir-based catalysts exhibit a reasonably effective NOx reduction (>80%) in the presence of O2 at temperatures ranging from 250–450 °C [105].

Unreacted ammonia slip in the tailpipe is another concern for the urea-SCR system. The ammonia slip can be caused by multiple factors including gradual reduction of NH3 storage efficiency of SCR due to aging, overdosing of urea, and spontaneous uncontrolled NH3 emission from urea crystal at high temperatures [106]. Ammonia slip catalyst (ASC) or cleanup catalyst is positioned downstream of the SCR catalyst to oxidize any unreacted ammonia slipped past the SCR to N2 according to the following reaction [86,107]:

However, it should be noted that the selectivity of this reaction is not high enough to achieve complete conversion and possible side reactions involving NO and N2O as products can occur [108].

3. Cold-Start/Low Temperature Challenges

Emission control during engine cold-start is an ongoing challenge for the automotive industry because of unfavourable boundary conditions, such as low fuel injection pressure, low in-cylinder temperature and pressure, weak in-cylinder flow intensity and a sub-optimal operation of catalytic converters. Studies have reported up to 88% higher NOx emission during cold start as compared to the average engine operation [109,110]. The inferior performance of the aftertreatment system predominantly arises from the low catalytic activity, availability of reducing agents and urea crystal depositions. Different strategies to tackle these challenges have been investigated including engine operation modulation to reduce the catalyst warm-up time before light-off, the addition of supplemental catalysts in close-coupled position with the engine, higher PGM loading to reduce light-off temperature, replacement of reducing agents with superior low-temperature characteristics, the addition of low-temperature NOx adsorber catalysts and active catalyst heating.

Adding an additional SCR-ASC system in a close-coupled position with the engine before the conventional aftertreatment system chain has been reported to reduce the cold-start NOx emissions by 90% and N2O emissions by 20% at a cost of ~3% increased fuel consumption [111]. Moreover, the close-coupled SCR can reach the injection temperature fairly quickly, reducing the cold start duration to less than 100 s. SCR-coated diesel particulate filters (sDPF) have been reported as another strategy to mitigate cold-start NOx emissions [112]. The main advantage of combined filters is the placement of the sDPF system immediately downstream of DOC to reduce the warm-up duration. Close-coupled LNT with an sDPF system has also been investigated as a viable strategy for improving cold-start emission performance [113].

When evaluating engine operation aimed at rapidly increasing the aftertreatment system temperature, the impact on the fuel penalty and emission behaviour of the engine needs to be considered. A combination of cylinder deactivation and modulation of exhaust valve opening with late injections is shown to increase the turbine out exhaust temperature by 50 °C–150 °C achieving, at the same time, about a 6% reduction in fuel consumption [114]. The same approach implemented on an X15 6-cylinder Cummins engine with variable geometry turbine (VGT) and high-pressure exhaust gas recirculation (EGR), resulted in an increase of 40 °C–100 °C to the turbo-out temperature, together with a simulated reduction of NOx and CO2 emissions by 74% and 5%, respectively [115].

A heated injection system, combined with a hydrolysis catalyst constitutes another pathway to accelerate hydrolysis and ammonia release from the urea injection in SCR systems. Kowatari et al. investigated an aftertreatment system configuration where a portion of the exhaust stream is redirected to an electrically heated bypass equipped with a dedicated injector [116]. This process involves initially heating the flow for urea thermolysis, followed by a hydrolysis catalyst to complete the decomposition. While this approach achieves NOx conversions of up to 99% at 160 °C, it comes with certain drawbacks such as fuel penalties associated with electrical energy consumption.

Sharp et al. investigated the addition of a 2 kW electrically heated catalyst, followed by a hydrolysis catalyst, along with an additional 5 kW heater positioned downstream of the DPF and before the urea injection point [117]. The authors reported an 80% reduction in NOx emissions, albeit at the cost of elevated energy consumption attributed to the heaters.

4. Ultra-Low NOx Future—Towards Euro VII and EPA2027

Aftertreatment systems constitute an integral part of emission control in vehicular and stationary applications. The efficacy of various NOx aftertreatment technologies has improved tremendously in past decades. Once warmed up, TWC, LNT, and SCR catalysts can achieve impressive NOx conversion efficiencies of 90% and above. Cold-start remains a real challenge not only for aftertreatment systems but engine research as a whole. The high conversion efficiencies of the catalytic converters further highlight the fact that the present, single-stage NOx reduction solutions may not be able to fulfill the stringent NOx reduction mandates of the upcoming emission regulations. To meet the stricter Euro VII and EPA2027 emission regulations, a combination of the multiple NOx after-treatment technologies coupled with the in-cylinder NOx control will be necessary.

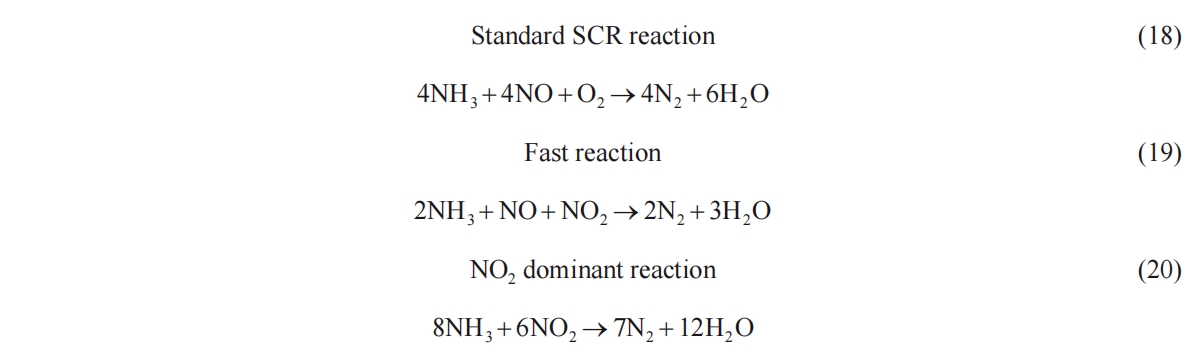

Figure 8 shows some of the proposed aftertreatment solutions for diesel and gasoline engines for upcoming emission regulations [13]. Exploiting different NOx reduction catalysts for specific applications including cold-start emissions (using close-coupled catalysts and active catalyst heating), mitigation of previously unregulated compounds such as NH3 (using cleanup catalyst) and N2O (by improving the low-temperature catalytic performance) will be indispensable for further reduction of tailpipe NOx emissions.

Figure 8. Proposed aftertreatment system design for further NOx reduction to meet Euro VII and EPA2027 emission standards.

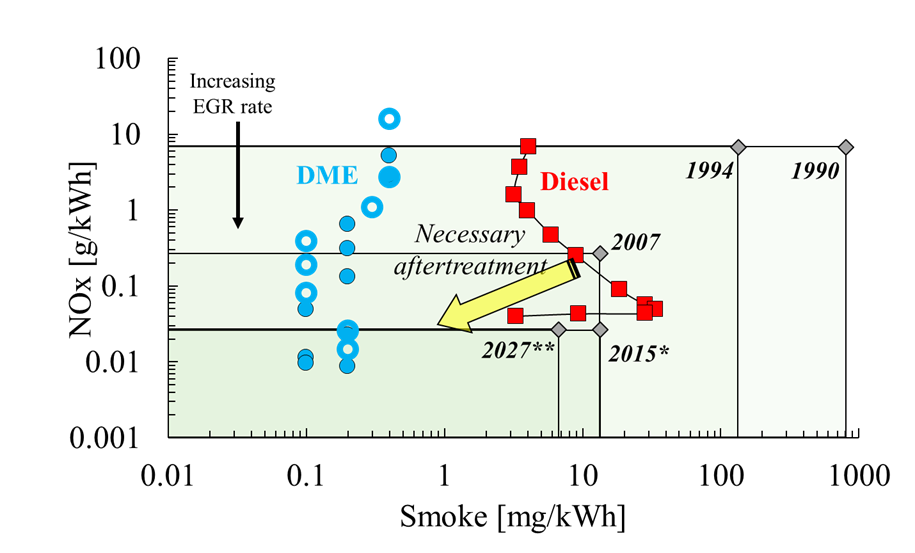

In-cylinder NOx control using lean burn and EGR dilution has been well-researched and implemented technology for IC engines. Reduction of in-cylinder NOx formation presents the most economical and least complex pathway in terms of emission control system design. Diesel combustion is prone to the inherent soot-NOx trade-off that limits the applicability of EGR for NOx control. The use of oxygenated alternative fuels like DME, which suppresses the soot formation, can not only aid in reducing the carbon footprint of the IC engine but also allow using higher EGR rates for NOx mitigation (Figure 9) [118]. Additionally, lower combustion temperature from in-cylinder NOx mitigation strategies reduces the thermal stress on the aftertreatment system at higher loads, potentially slowing the thermal aging.

Figure 9. The NOx-smoke trade-off of diesel compared with DME. All emissions are engine-out. 2015*: Optional US California HD certification. 2027**: Proposed EPA2027. [118].

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation: N.S., X.Y.; software, validation, resources, writing—original draft preparation, visualization, N.S.; data curation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing: X.Y., M.Z.; supervision, project administration: M.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement: Not applicable.

Acknowledgments: The research at the Clean Combustion Engine Laboratory is partially sponsored by: Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC)—Industrial Research Chairs Grants (IRC), Collaborative Research and Development Grants (CRD), Research Tools and Instruments grants program (RTI), Discovery Grants (individual) program (DG); Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI)—Ontario Research Foundation (ORF); and the University of Windsor. Special thanks to Original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) for their support, and Clean Combustion Engine Lab (CCEL) colleagues’ contribution in their time.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yu, X.; Sandhu, N.S.; Yang, Z.; Zheng, M. Suitability of energy sources for automotive application—A review. Applied Energy 2020, 271, 115169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.115169. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.115169

- Yu, X.; LeBlanc, S.; Sandhu, N.; Wang, L.; Wang, M.; Zheng, M. Decarbonization potential of future sustainable propulsion—A review of road, transportation. Energy Science & Engineering 2023, 237. https://doi.org/10.1002/ese3.1434. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/ese3.1434

- Ribeiro, C.B.; Rodella, F.H.C.; Hoinaski, L. Regulating light-duty vehicle emissions: an overview of US, EU, China and Brazil programs and its effect on air quality. Clean Techn Environ Policy 2022, 24(3), 851–862. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-021-02238-1 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-021-02238-1

- Dieselnet. Emission Standards: USA: Heavy-Duty Onroad Engines. Available online: https://dieselnet.com/standards/us/hd.php (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Dieselnet. Emission Standards: USA: Cars and Light-Duty Trucks—Tier 1. Available online: https://dieselnet.com/standards/us/ld.php (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Dieselnet. Emission Standards: USA: Cars and Light-Duty Trucks—Tier 2. Available online: https://dieselnet.com/standards/us/ld_t2.php (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Dieselnet. Emission Standards: USA: Cars and Light-Duty Trucks—Tier 3. Available online: https://dieselnet.com/standards/us/ld_t3.php (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- ISBN 978-92-76-58723-1; Euro 7 Standards: New Rules for Vehicle Emissions. Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022.

- US EPA. EPA-HQ-OAR-2022-0829; Multi-Pollutant Emissions Standards for Model Years 2027 and Later LightDuty and Medium-Duty Vehicles. US Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2023.

- Williams, M.; Minjares, R. A Technical Summary of Euro 6/VI Vehicle Emission Standards; The international Council on Clean Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- US EPA. “Gasoline Sulfur” Overviews and Factsheets. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/gasoline-standards/gasoline-sulfur (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Dieselnet. Emission Standards: Europe: Heavy-Duty Truck and Bus Engines. Available online: https://dieselnet.com/standards/eu/hd.php (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Selleri, T.; Melas A.D.; Joshi A.; Manara D.; Perujo A.; Suarez-Bertoa, R. An Overview of Lean Exhaust deNOx Aftertreatment Technologies and NOx Emission Regulations in the European Union. Catalysts 2021, 11(3), 404. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal11030404. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/catal11030404

- Granger, P.; Parvulescu, V.I. Catalytic NOx Abatement Systems for Mobile Sources: From Three-Way to Lean Burn after-Treatment Technologies. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111(5), 3155–3207. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr100168g. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/cr100168g

- European Marine Safety Agency. Facts and Figures: The EMTER Report; European Environment Agency: Lisboa, Portugal, 2021.

- Mohd Noor, C.W.; Noor, M.M.; Mamat, R. Biodiesel as alternative fuel for marine diesel engine applications: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 94, 127–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.05.031. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.05.031

- Ni, P.; Wang, X.; Li, H. A review on regulations, current status, effects and reduction strategies of emissions for marine diesel engines. Fuel 2020, 279, 118477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118477. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118477

- Dieselnet. Emission Standards: USA: Locomotives. Available online: https://dieselnet.com/standards/us/loco.php (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Zannis, T.C.; Katsanis, J.S.; Christopoulos, G.P.; Yfantis, E.A.; Papagiannakis, R.G.; Pariotis, E.G.; Rakopoulos, D.C.; Rakopoulos, C.D.; Vallis, A.G. Marine Exhaust Gas Treatment Systems for Compliance with the IMO 2020 Global Sulfur Cap and Tier III NOx Limits: A Review. Energies 2022, 15(10), 3638. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15103638. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/en15103638

- Yanai, T.; Han, X.; Zheng, M. Extension of Diesel Engine Load Range with Simultaneous Reduction of NOx and Soot by using Ethanol Port Injection, High Intake Boost and EGR. Transactions of Society of Automotive Engineers of Japan 2013, 44(5), 1169–1174. https://doi.org/10.11351/jsaeronbun.44.1169.

- Zheng, M.; Reader, G.T.; Hawley, J.G. Diesel engine exhaust gas recirculation––a review on advanced and novel concepts. Energy Conversion and Management 2004, 45(6), 883–900. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0196-8904(03)00194-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0196-8904(03)00194-8

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Lei, X.; Liu, S. Combustion and emission characteristics of a DME (dimethyl ether)-diesel dual fuel premixed charge compression ignition engine with EGR (exhaust gas recirculation). Energy 2014, 72, 608–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2014.05.086. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2014.05.086

- Piumetti, M.; Bensaid, S.; Fino, D.; Russo, N. Catalysis in Diesel engine NOx aftertreatment: A review. Catalysis, Structure & Reactivity 2015, 1(4), 155–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/2055074X.2015.1105615. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/2055074X.2015.1105615

- Imanaka, N.; Masui, T. Advances in direct NOx decomposition catalysts. Applied Catalysis A: General 2012, 431–432, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcata.2012.02.047. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcata.2012.02.047

- Germane, G.J.; Wood, C.G.; Hess, C.C. Lean Combustion in Spark-Ignited Internal Combustion Engines—A Review; SAE Technical Paper 831694; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1983. https://doi.org/10.4271/831694. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4271/831694

- Wei, H.; Zhu, T.; Shu, G.; Tan, L.; Wang, Y. Gasoline engine exhaust gas recirculation—A review. Applied Energy 2012, 99, 534–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2012.05.011. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2012.05.011

- Penetrante, B.M.; Brusasco, R.M.; Merritt, B.T.; Pitz, W.J.; Vogtlin, G.E.; Kung, M.C.; Kung, H.H.; Wan, C.Z.; Voss, K.E. Plasma-Assisted Catalytic Reduction of NOx. SAE Transactions 1998, 107, 1222–1231,. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4271/982508

- Zhang, Z.; Shi, C.; Bai, Z.; Li, M.; Chen, B.; Crocker, M. Low-temperature H2-plasma-assisted NOx storage and reduction over a combined Pt/Ba/Al and LaMnFe catalyst. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2017, 7(1), 145–158. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6CY01900E. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/C6CY01900E

- Ko, B.H., Hasa, B., Shin, H., Zhao, Y., and Jiao, F., “Electrochemical Reduction of Gaseous Nitrogen Oxides on Transition Metals at Ambient Conditions,” J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144(3):1258–1266, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.1c10535. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.1c10535

- Wan, H.; Bagger, A.; Rossmeisl, J. Electrochemical Nitric Oxide Reduction on Metal Surfaces. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2021, 60(40), 21966–21972. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202108575. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202108575

- Kašpar, J.; Fornasiero, P.; Hickey, N. Automotive catalytic converters: Current status and some perspectives. Catalysis Today 2003, 77(4), 419–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-5861(02)00384-X. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-5861(02)00384-X

- Taylor, K.C. Automobile Catalytic Converters. In Catalysis: Science and Technology; Anderson, J.R., Boudart, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984; Volume 5, pp. 119–170; ISBN 978-3-642-93247-2. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-93247-2_2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-93247-2_2

- Rood, S.; Eslava, S.; Manigrasso, A.; Bannister, C. Recent advances in gasoline three-way catalyst formulation: A review. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part D: Journal of Automobile Engineering 2020, 234(4), 936–949. https://doi.org/10.1177/0954407019859822. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0954407019859822

- Sandhu, N.S.; Leblanc, S.; Yu, X.; Reader, G.; Zheng, M. Characterization of an Integrated Three-Way Catalyst/Lean NOx Trap System for Lean Burn SI Engines. In SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2023; No. 2023-01–1658. https://doi.org/10.4271/2023-01-1658. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4271/2023-01-1658

- Mera, Z.; Fonseca, N.; Casanova, J.; López, J.-M. Influence of exhaust gas temperature and air-fuel ratio on NOx aftertreatment performance of five large passenger cars. Atmospheric Environment 2021, 244, 117878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.117878. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.117878

- Baron, J.H.; Cheng, W.K. Back pressure effect on three-way catalyst light-off. International Journal of Engine Research 2019, 20(7), 726–733. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468087418779505. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1468087418779505

- Watling, T.C.; Cox, J.P. Factors Affecting Three-Way Catalyst Light-Off: A Simulation Study. SAE Int. J. Engines 2014, 7(3), 1311–1325. https://doi.org/10.4271/2014-01-1564. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4271/2014-01-1564

- Pârvulescu, V.I.; Grange, P.; Delmon, B. Catalytic removal of NO. Catalysis Today 1998, 46(4), 233–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-5861(98)00399-X. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-5861(98)00399-X

- Shelef, M.; Graham, G.W. Why Rhodium in Automotive Three-Way Catalysts? Catalysis Reviews 1994, 36(3), 433–457, https://doi.org/10.1080/01614949408009468. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01614949408009468

- Engler, B.H.; Lox, E.S.; Ostgathe, K.; Ohata, T.; Tsuchitani, K.; Ichihara, S.; Onoda, H.; Garr, G.T.; Psaras, D. Recent Trends in the Application of Tri-Metal Emission Control Catalysts. In SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1994; No. 940928. https://doi.org/10.4271/940928. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4271/940928

- Collins, N.R.; Twigg, M.V. Three-way catalyst emissions control technologies for spark-ignition engines—Recent trends and future developments. Top. Catal. 2007, 42(1), 323–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11244-007-0199-6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11244-007-0199-6

- Yamamoto, M.; Tanaka, H. Influence of Support Materials on Durability of Palladium in Three-Way Catalyst. In SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1998; No. 980664. https://doi.org/10.4271/980664. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4271/980664

- Bakker, J.M.; Mafuné, F. Zooming in on the initial steps of catalytic NO reduction using metal clusters. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24(13), 7595–7610. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1CP05760J. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/D1CP05760J

- Haneda, M.; Kaneko, T.; Kamiuchi, N.; Ozawa, M. Improved three-way catalytic activity of bimetallic Ir–Rh catalysts supported on CeO2–ZrO2. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2015, 5(3), 1792–1800. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4CY01502A. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/C4CY01502A

- Vedyagin, A.A.; Gavrilov, M.S.; Volodin, A.M.; Stoyanovskii, V.O.; Slavinskaya, E.M.; Mishakov, I.V.; Shubin, Y.V. Catalytic Purification of Exhaust Gases Over Pd–Rh Alloy Catalysts. Top. Catal. 2013, 56(11), 1008–1014. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11244-013-0064-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11244-013-0064-8

- Twigg, M.V. Catalytic control of emissions from cars. Catalysis Today 2011, 163(1), 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2010.12.044. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2010.12.044

- Montini, T.; Melchionna, M.; Monai, M.; Fornasiero, P. Fundamentals and Catalytic Applications of CeO2-Based Materials. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116(10), 5987–6041. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00603. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00603

- Sobukawa, H. Development of ceria-zirconia solid solutions and future trends. R&D Reviews Toyota CRDL 2020, 37, 1–5,.

- Sugiura, M. Oxygen Storage Materials for Automotive Catalysts: Ceria-Zirconia Solid Solutions. Catalysis Surveys from Asia 2003, 7(1), 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023488709527. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023488709527

- Si, R.; Zhang, Y.-W.; Wang, L.-M.; Li, S.-J.; Lin, B.-X.; Chu, W.-S.; Wu, Z.-Y.; Yan, C.-H. Enhanced Thermal Stability and Oxygen Storage Capacity for CexZr1−xO2 (x = 0.4−0.6) Solid Solutions by Hydrothermally Homogenous Doping of Trivalent Rare Earths. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111(2), 787–794. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp0630875. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/jp0630875

- Li, J.; Liu, X.; Zhan, W.; Guo, Y.; Guo, Y.; Lu, G. Preparation of high oxygen storage capacity and thermally stable ceria–zirconia solid solution. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6(3), 897–907. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5CY01571E. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/C5CY01571E

- Cant, N.W.; Angove, D.E.; Chambers, D.C. Nitrous oxide formation during the reaction of simulated exhaust streams over rhodium, platinum and palladium catalysts. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 1998, 17(1), 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0926-3373(97)00105-7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0926-3373(97)00105-7

- Kim, S.; D’Aniello, M.J. Analytical electron microscopy study of two vehicle-aged automotive exhaust catalysts having dissimilar activities. Applied Catalysis 1989, 56(1), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-9834(00)80156-6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-9834(00)80156-6

- Monte, R.D.; Fornasiero, P.; Kašpar, J.; Graziani, M.; Gatica, J.M.; Bernal, S.; Gómez-Herrero, A. Stabilisation of nanostructured Ce0.2Zr0.8O2 solid solution by impregnation on Al2O3: A suitable method for the production of thermally stable oxygen storage/release promoters for three-way catalysts. Chem. Commun. 2000, 21, 2167–2168. https://doi.org/10.1039/B006674P. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/b006674p

- Angelidis, T.N.; Koutlemani, M.M.; Sklavounos, S.A.; Lioutas, Ch.B.; Voulgaropoulos, A.; Papadakis, V.G.; Emons, H. Causes of deactivation and an effort to regenerate a commercial spent three-way catalyst. In Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis; Kruse, N., Frennet, A., Bastin, J.-M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1998; pp. 155–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2991(98)80873-2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2991(98)80873-2

- Williamson, W.B.; Perry, J.; Gandhi, H.S.; Bomback, J.L. Effects of oil phosphorus on deactivation of monolithic three-way catalysts. Applied Catalysis 1985, 15(2), 277–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-9834(00)81842-4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-9834(00)81842-4

- Cheekatamarla, P.K.; Lane, A.M. Catalytic autothermal reforming of diesel fuel for hydrogen generation in fuel cells: II. Catalyst poisoning and characterization studies. Journal of Power Sources 2006, 154(1), 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2005.04.011. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2005.04.011

- Cai, H.; Liu, Y.; Gong, J.; E, J.; Geng, Y.; Yu, L. Sulfur poisoning mechanism of three way catalytic converter and its grey relational analysis. J. Cent. South Univ. 2014, 21(11), 4091–4096. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11771-014-2402-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11771-014-2402-9

- Truex, T.J. Interaction of Sulfur with Automotive Catalysts and the Impact on Vehicle Emissions—A Review. SAE Transactions 1999, 108, 1192–1206,. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4271/1999-01-1543

- Koltsakis, G.C.; Alexiadou, P.; Avgerinos, C.; Symeonidis, N.; Nagano, S.; Lafossas, F.-A. Reversible Sulfur Poisoning of 3-way Catalyst linked with Oxygen Storage Mechanisms. In SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2021; No. 2021-24–0069. https://doi.org/10.4271/2021-24-0069. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4271/2021-24-0069

- Takahashi, N.; Shinjoh, H.; Iijima, T.; Suzuki, T.; Yamazaki, K.; Yokota, K.; Suzuki, H.; Miyoshi, N.; Matsumoto, S.; Tanizawa, T.; et al. The new concept 3-way catalyst for automotive lean-burn engine: NOx storage and reduction catalyst. Catalysis Today 1996, 27(1), 63–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/0920-5861(95)00173-5. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0920-5861(95)00173-5

- Choi, B.; Lee, K.; Son, G. Review of Recent After-Treatment Technologies for De-NOx Process in Diesel Engines. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2020, 21(6), 1597–1618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12239-020-0150-4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12239-020-0150-4

- Václavík, M.; Novák, V.; Březina, J.; Kočí, P.; Gregori, G.; Thompsett, D. Effect of diffusion limitation on the performance of multi-layer oxidation and lean NOx trap catalysts. Catalysis Today 2016, 273, 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2016.03.013. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2016.03.013

- Roy, S.; Baiker, A. NOx Storage-Reduction Catalysis: From Mechanism and Materials Properties to Storage-Reduction Performance. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109(9), 4054–4091. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr800496f. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/cr800496f

- Aversa, C.; Yu, S.; Jeftić, M.; Bryden, G.; Zheng, M. Long breathing lean NOx trap regeneration with supplemental n-butanol. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part D: Journal of Automobile Engineering 2019, 233(3), 661–670. https://doi.org/10.1177/0954407017752225. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0954407017752225

- Jeftic, M. Strategies for Enhanced After-Treatment Performance: Post Injection Characterization and Long Breathing with Low NOx Combustion. Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2016.

- de Ojeda, W.; Zheng, M.; Han, X.; Jeftic, M.; Wang, M. Diesel Engine NOx Reduction. US-20150113961-A1, 2015.

- Chaugule, S.S.; Yezerets, A.; Currier, N.W.; Ribeiro, F.H.; Delgass, W.N. ‘Fast’ NOx storage on Pt/BaO/γ-Al2O3 Lean NOx Traps with NO2+O2 and NO+O2: Effects of Pt, Ba loading. Catalysis Today 2010, 151(3), 291–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2010.02.024. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2010.02.024

- Ji, Y.; Choi, J.-S.; Toops, T.J.; Crocker, M.; Naseri, M. Influence of ceria on the NOx storage/reduction behavior of lean NOx trap catalysts. Catalysis Today 2008, 136(1), 146–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2007.11.059. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2007.11.059

- Lv, L.; Wang, X.; Shen, M.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J. The lean NOx traps behavior of (1–5%) BaO/CeO2 mixed with Pt/Al2O3 at low temperature (100–300 °C): The effect of barium dispersion. Chemical Engineering Journal 2013, 222, 401–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2013.02.084. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2013.02.084

- Wang, X.; Yu, Y.; He, H. Effects of temperature and reductant type on the process of NOx storage reduction over Pt/Ba/CeO2 catalysts. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2011, 104(1), 151–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2011.02.018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2011.02.018

- Ji, Y.; Toops, T.J.; Crocker, M. Effect of Ceria on the Storage and Regeneration Behavior of a Model Lean NOx Trap Catalyst. Catal. Lett. 2007, 119(3), 257–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10562-007-9226-2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10562-007-9226-2

- DiGiulio, C.D.; Pihl, J.A.; Choi, J.-S.; Parks, J.E.; Lance, M.J.; Toops, T.J.; Amiridis, M.D. NH3 formation over a lean NOX trap (LNT) system: Effects of lean/rich cycle timing and temperature. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2014, 147, 698–710, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2013.09.012. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2013.09.012

- Epling, W.S.; Campbell, L.E.; Yezerets, A.; Currier, N.W.; Parks, J.E. Overview of the Fundamental Reactions and Degradation Mechanisms of NOx Storage/Reduction Catalysts. Catalysis Reviews 2004, 46(2), 163–245. https://doi.org/10.1081/CR-200031932. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1081/CR-200031932

- Pihl, J.A.; Parks, J.E.; Daw, C.S.; Root, T.W. Product Selectivity During Regeneration of Lean NOx Trap Catalysts. SAE Transactions 2006, 115, 947–960. https://doi.org/10.4271/2006-01-3441. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4271/2006-01-3441

- Hackenberg, S.; Ranalli, M. Ammonia on a LNT: Avoid the Formation or Take Advantage of It. In SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2007; No. 2007-01–1239. https://doi.org/10.4271/2007-01-1239. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4271/2007-01-1239

- Rohr, F.; Peter, S.D.; Lox, E.; Kögel, M.; Müller, W.; Sassi, A.; Rigaudeau, C.; Juste, L.; Belot, G.; Gélin, P.; et al. The Impact of Sulfur Poisoning on NOx-Storage Catalysts in Gasoline Applications. SAE Transactions 2005, 114, 594–603. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4271/2005-01-1113

- Sedlmair, C.; Seshan, K.; Jentys, A.; Lercher, J.A. Studies on the deactivation of NOx storage-reduction catalysts by sulfur dioxide. Catalysis Today 2002, 75(1), 413–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-5861(02)00091-3. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-5861(02)00091-3

- Engström, P.; Amberntsson, A.; Skoglundh, M.; Fridell, E.; Smedler, G. Sulphur dioxide interaction with NOx storage catalysts. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 1999, 22(4), L241–L248. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0926-3373(99)00060-0. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0926-3373(99)00060-0

- Cichanowicz, J.; Muzio, L. Twenty-Five Years of SCR Evolution: Implications For US Application And Operation. In Proceedings of the EPRI-DOE-EPA Combined Power Plant Air Pollutant Control Symposium: The MEGA Symposium, Chicago, IL, USA, 2001; pp. 20–23.

- Forzatti, P.; Lietti, L.; Tronconi, E. Nitrogen Oxides Removal—Industrial. In Encyclopedia of Catalysis; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-471-22761-8. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471227617.eoc155.pub2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/0471227617.eoc155.pub2

- ACEA. ACEA Statement on the Adoption of SCR Technology to Reduce Emissions Levels of Heavy-Duty Vehicles. ACEA Position Paper, 15 July 2003.

- Kleemann, M.; Elsener, M.; Koebel, M.; Wokaun, A. Hydrolysis of Isocyanic Acid on SCR Catalysts. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2000, 39(11), 4120–4126. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie9906161. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/ie9906161

- Birkhold, F.; Meingast, U.; Wassermann, P.; Deutschmann, O. Modeling and simulation of the injection of urea-water-solution for automotive SCR DeNOx-systems. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2007, 70(1), 119–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2005.12.035. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2005.12.035

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Shao, S.; Li, M. Numerical analysis on the mixing and urea crystallization characteristics in the SCR system. Chemical Engineering and Processing—Process Intensification 2022, 171, 108715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cep.2021.108715. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cep.2021.108715

- Maunula, T.; Tuikka, M.; Wolff, T. The Reactions and Role of Ammonia Slip Catalysts in Modern Urea-SCR Systems. Emiss. Control Sci. Technol. 2020, 6(4), 390–401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40825-020-00171-1. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40825-020-00171-1

- Yim, S.D.; Kim, S.J.; Baik, J.H.; Nam, I.; Mok, Y.S.; Lee, J.-H.; Cho, B.K.; Oh, S.H. Decomposition of Urea into NH3 for the SCR Process. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2004, 43(16), 4856–4863. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie034052j. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/ie034052j

- Mohan, S.; Dinesha, P.; Kumar, S. NOx reduction behaviour in copper zeolite catalysts for ammonia SCR systems: A review. Chemical Engineering Journal 2020, 384, 123253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2019.123253. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2019.123253

- Iwasaki, M.; Shinjoh, H. A comparative study of ‘standard’, ‘fast’ and ‘NO2′ SCR reactions over Fe/zeolite catalyst. Applied Catalysis A: General 2010, 390(1), 71–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcata.2010.09.034. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcata.2010.09.034

- Ciardelli, C.; Nova, I.; Tronconi, E.; Chatterjee, D.; Bandl-Konrad, B.; Weibel, M.; Krutzsch, B. Reactivity of NO/NO2–NH3 SCR system for diesel exhaust aftertreatment: Identification of the reaction network as a function of temperature and NO2 feed content. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2007, 70(1), 80–90, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2005.10.041. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2005.10.041

- Chundru, V.R.; Parker, G.G.; Johnson, J.H. The Effect of NO2/NOx Ratio on the Performance of a SCR Downstream of a SCR Catalyst on a DPF. SAE International Journal of Fuels and Lubricants 2019, 12(2), 121–142,. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4271/04-12-02-0008

- Yu, X.; Yu, S.; Zheng, M. Hydrocarbon impact on NO to NO2 conversion in a compression ignition engine under low-temperature combustion. International Journal of Engine Research 2019, 20(2), 216–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468087417745441. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1468087417745441

- Forzatti, P.; Nova, I.; Tronconi, E. New ‘Enhanced NH3-SCR’ Reaction for NOx Emission Control. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 49(21), 10386–10391. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie100600v. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/ie100600v

- Cheng, X.; Bi, X.T. A review of recent advances in selective catalytic NOx reduction reactor technologies. Particuology 2014, 16, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.partic.2014.01.006. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.partic.2014.01.006

- Kröcher, O. Chapter 9 Aspects of catalyst development for mobile urea-SCR systems—From Vanadia-Titania catalysts to metal-exchanged zeolites. In Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis; Granger, P., Pârvulescu, V.I., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2007; pp. 261–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2991(07)80210-2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2991(07)80210-2

- Wang, A.; Wang, Y.; Walter, E.D.; Washton, N.M.; Guo, Y.; Lu, G.; Peden, C.H.F.; Gao, F. NH3-SCR on Cu, Fe and Cu+Fe exchanged beta and SSZ-13 catalysts: Hydrothermal aging and propylene poisoning effects. Catalysis Today 2019, 320, 91–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2017.09.061. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2017.09.061

- Song, J.; Wang, Y.; Walter, E.D.; Washton, N.M.; Mei, D.; Kovarik, L.; Engelhard, M.H.; Prodinger, S.; Wang, Y.; Peden, C.H.F.; et al. Toward Rational Design of Cu/SSZ-13 Selective Catalytic Reduction Catalysts: Implications from Atomic-Level Understanding of Hydrothermal Stability. ACS Catal. 2017, 7(12), 8214–8227. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.7b03020. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.7b03020

- Cui, Y.; Wang, Y.; Mei, D.; Walter, E.D.; Washton, N.M.; Holladay, J.D.; Wang, Y.; Szanyi, J.; Peden, C.H.F.; Gao, F. Revisiting effects of alkali metal and alkaline earth co-cation additives to Cu/SSZ-13 selective catalytic reduction catalysts. Journal of Catalysis 2019, 378, 363–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcat.2019.08.028. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcat.2019.08.028

- Xu, R.; Wang, Z.; Liu, N.; Dai, C.; Zhang, J.; Chen, B. Understanding Zn Functions on Hydrothermal Stability in a One-Pot-Synthesized Cu&Zn-SSZ-13 Catalyst for NH3 Selective Catalytic Reduction. ACS Catal. 2020, 10(11), 6197–6212. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.0c01063. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.0c01063

- Ma, L.; Su, W.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Fu, L.; Hao, J. Mechanism of propene poisoning on Cu-SSZ-13 catalysts for SCR of NOx with NH3. Catalysis Today 2015, 245, 16–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2014.05.027. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2014.05.027

- Luo, J.-Y.; Oh, H.; Henry, C.; Epling, W. Effect of C3H6 on selective catalytic reduction of NOx by NH3 over a Cu/zeolite catalyst: A mechanistic study. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2012, 123–124, 296–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2012.04.038. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2012.04.038

- Lee, K.; Kosaka, H.; Sato, S.; Yokoi, T.; Choi, B. Effect of Cu content and zeolite framework of n-C4H10-SCR catalysts on de-NOx performances. Chemical Engineering Science 2019, 203, 28–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2019.03.028. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2019.03.028

- Erkfeldt, S.; Palmqvist, A.; Petersson, M. Influence of the reducing agent for lean NOx reduction over Cu-ZSM-5. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2011, 102(3), 547–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2010.12.037. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2010.12.037

- Hamada, H.; Haneda, M. A review of selective catalytic reduction of nitrogen oxides with hydrogen and carbon monoxide. Applied Catalysis A: General 2012, 421–422, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcata.2012.02.005. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcata.2012.02.005

- Takahashi, A.; Fujitani, T.; Nakamura, I.; Katsuta, Y.; Haneda, M.; Hamada, H. Excellent Promoting Effect of Ba Addition on the Catalytic Activity of Ir/WO3–SiO2 for the Selective Reduction of NO with CO. Chemistry Letters 2006, 35(4), 420–421. https://doi.org/10.1246/cl.2006.420. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1246/cl.2006.420

- Yue, G.; Qiu, T.; Lei, Y. Experimental demonstration of NOx reduction and ammonia slip for diesel engine SCR system. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29(1), 1118–1133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-15592-w. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-15592-w

- Girard, J.W.; Cavataio, G.; Lambert, C.K. The Influence of Ammonia Slip Catalysts on Ammonia, N₂O and NOx Emissions for Diesel Engines. SAE Transactions 2007, 116, 182–186,. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4271/2007-01-1572

- Colombo, M.; Nova, I.; Tronconi, E.; Schmeißer, V.; Bandl-Konrad, B.; Zimmermann, L. Experimental and modeling study of a dual-layer (SCR+PGM) NH3 slip monolith catalyst (ASC) for automotive SCR aftertreatment systems. Part 1. Kinetics for the PGM component and analysis of SCR/PGM interactions. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2013, 142–143, 861–876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2012.10.031. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2012.10.031

- Lee, D.-W.; Johnson, J.; Lv, J.; Novak, K.; Zietsman, J. Comparisons Between Vehicular Emissions From Real-World In-Use Testing And Epa Moves Estimation; Technical Report SWUTC/12/476660-00021-1, Texas Transportation Institute; The Texas A&M University: College Station, TX, USA, 2012.

- Reiter, M.S.; Kockelman, K.M. The problem of cold starts: A closer look at mobile source emissions levels. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2016, 43, 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2015.12.012. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2015.12.012

- Adelman, B.; Singh, N.; Charintranond, P.; Manis, J. Achieving Ultra-Low NOx Tailpipe Emissions with a High Efficiency Engine. In SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2020; No. 2020-01–1403. https://doi.org/10.4271/2020-01-1403. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4271/2020-01-1403

- Castoldi, L. An Overview on the Catalytic Materials Proposed for the Simultaneous Removal of NOx and Soot. Materials 2020, 13(16), 3551. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13163551. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13163551

- Auld, A.; Ward, A.; Mustafa, K.; Hansen, B. Assessment of Light Duty Diesel After-Treatment Technology Targeting Beyond Euro 6d Emissions Levels. SAE Int. J. Engines 2017, 10(4), 1795–1807. https://doi.org/10.4271/2017-01-0978. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4271/2017-01-0978

- Vos, K.R.; Shaver, G.M.; Joshi, M.C.; McCarthy, J. Implementing variable valve actuation on a diesel engine at high-speed idle operation for improved aftertreatment warm-up. International Journal of Engine Research 2020, 21(7), 1134–1146. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468087419880639. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1468087419880639

- Srinivasan, V.; Wolk, B.; Cai, X.; Henrichsen, L.; Lee, J.; Patil, D. Application of Dynamic Skip Fire for NOx and CO2 Emissions Reduction of Diesel Powertrains. SAE Int. J. Adv. & Curr. Prac. Mobility 2021, 4(1), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.4271/2021-01-0450. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4271/2021-01-0450

- Kowatari, T.; Hamada, Y.; Amou, K.; Hamada, I.; Funabashi, H.; Takakura, T.; Nakagome, K. A Study of a New Aftertreatment System (1): A New Dosing Device for Enhancing Low Temperature Performance of Urea-SCR. SAE Transactions 2006, 115, 244–251. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4271/2006-01-0642

- Sharp, C.; Webb, C.C.; Neely, G.; Carter, M.; Yoon, S.; Henry, C. Achieving Ultra Low NO X Emissions Levels with a 2017 Heavy-Duty On-Highway TC Diesel Engine and an Advanced Technology Emissions System—Thermal Management Strategies. SAE Int. J. Engines 2017, 10(4), 1697–1712. https://doi.org/10.4271/2017-01-0954. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4271/2017-01-0954

- LeBlanc, S.; Yu, X.; Wang, L.; Zheng, M. Dimethyl Ether to Power Next-Generation Road Transportation. IJAMM 2023, 2, 3. https://doi.org/10.53941/ijamm.2023.100003. DOI: https://doi.org/10.53941/ijamm.2023.100003